How To Party with Isaac Hindin-Miller

...if you can. My conversation with the DJ and influencer on MANHATTANISM, TOUGH DOORS, PARTYING WITH MODELS and NIGHTLIFE REALISM

Photo credit: Max Tardio.

One of my best startup ideas is a cultural exchange program that lets people who go out in Brooklyn switch places with people who go out in Manhattan for a weekend.

Manhattan has its allure. For reasons that I really don’t want to get into, and that if you don’t know about, you’re better off not knowing (and I mean it), I’ve been reading a lot recently about supposed cultural developments in Manhattan. Which is befuddling to me, because as far as I know, there’s not a lot going on over there. And my sources are pretty well placed.

I’ve worked there, but never lived there. The closest I came was when I worked at NYU writing papers about Obamacare, while also doing a Master’s program where serial sexual harassers and their friends would assign us books and we would decide whether they were Marxist or Foucauldian. Despite my dual engagements with the island’s biggest landlord, I couldn’t afford to rent there, but I had a friend who worked at Facebook teaching computers how to sell ads. He lived in Nolita with three roommates, 2 in tech and one in investment banking, in a 4-bedroom that costed like $5500 a month. This was like 2016.

Since I had a desk, an academic department, a working NYU keycard and a place to crash, I hung around by Houston Street all day and night, hoping to find something cool to do. I liked leaving work and walking into gallery openings that served free wine, and holding back laughter at bad paintings, and then linking up with friends in some vanishing affordable corner of downtown that was too crowded, trying to find somewhere, anywhere that would play a Drake song, or something with some drums and some bass that would nourish us with a thrill, or just any scrap of culture worth absorbing that didn’t cost too much, where someone might say, “here the secret is! You found it! Congratulations, welcome.”

At the NYU office I worked in, I’d sometimes run into Jared Kushner’s brother in the elevator. Their family own the building, they were NYU’s landlord in that case. Anyway, the office was right across the street from the Supreme store, and instead of working, I’d take a walk to see the resellers and tourist kids wait in the line that curled around the block, before eventually even Supreme got priced out.

I empathize with believers who are inflating the idea of a Manhattan cultural moment: I’ve got a FOMO fantasy that’s always ballooning, even though I live just 20 minutes and $2.75 away, fed by a pandemic year without leaving Brooklyn. I want to believe, too, in there being something going on downtown that’s worth seeing.

I’ve always been extremely fascinated with the night-lives of Manhattanites with money. That’s what the cultural exchange start-up idea is: like, in exchange for explaining to an ibanker what Mood Ring is and how to go a whole night without groping anyone, your average Mood Ring goer would in turn get a baby blue-button-down-shirt, some hard-bottomed shoes, and be able to stomp them right over the Meatpacking District on a Friday night, and there’d be a table waiting for them wherever they’d go.

I thought of DJ and nightlife influencer Isaac Hindin-Miller as an icon of blue button-down shirt culture, but on the phone he corrected me: “that has nothing to do with the parties I throw at all.”

Isaac instead sees himself as part of a different breed of Manhattanite: “Cool kids,” went to his parties, he said, “downtown characters,” evoking a storied, glamorous lineage of Manhattan nightclubbers. So, I thought to myself when he said that, not ibankers or Qatari businessmen, but their daughters who go to FIT or NYU, and their boyfriends who work at Google and watch a lot of movies. That’s my judgement, to be clear. I just don’t think anyone can really afford to be a character downtown anymore.

There’s also a grass-is-always-greener thing, to be sure–Isaac derisively called out the venues I’d ask him about as “cool Brooklyn [places] that [he’s] never heard of before”–did he think that I thought the places I hang out were cooler? That’s precisely the opposite of my motivation.

Though I’m obviously a Manhattan skeptic, I really dreamt of hearing that there was something I was missing about Manhattan nightclubbing. I was hoping to hear that, though from the outside it may seem like its kind of hollow and fucked up, that there was actually a magic to it that defies that stereotype.

But when I caught up with Isaac between fashion weeks, well, he described a world that left me with a knot in my stomach. I’ll take an opportunity to reacquaint myself with my own discernment, and to remind myself that even beyond the velvet ropes, in the middle of the hype, there are things that are simply not my bag. Oh yeah, there’s Drake quote for this: “Fashion Week is more your thing than mine.”

Fashion Week feels like one of those things that is like, mandatory cultural knowledge, but relatively few people actually participate or know what it is. Like I’ve heard the phrase “Fashion Week” for at least 10 years of my life but I’m not actually sure I truly know what it is. What do you enjoy about fashion week?

Traditionally Fashion Week is all massive fashion shows and massive afterparties put on by these multi-billion dollar brands. But this time, arguably the best parties of the week came from these start up brands, and I would consider my own brand to be a part of this. We threw this really big party, Midnight Rodeo threw a really big party and Bashment did a really big party as well. All these much smaller start ups did the best parties of the week and really are competing against these massive brands and I think that’s a really exciting thing that’s happening in downtown New York City culture right now.

ADLAN: How are Fashion Week parties different from a regular club night?

ISAAC: Generally speaking, I would say that the difference between Fashion Week parties and regular parties are that Fashion Week parties are overrun with people and are generally terrible, and normal parties are great. Fashion Week can be like New Years Eve, where everybody’s trying to have the best night ever and whenever you’re trying really hard to have fun and chasing fun all over the city, it doesn’t lend itself to having a very good time.

Manhattan is scary to some people. Like, the idea is in Brooklyn you can do whatever, get in wearing whatever. One of the things I think is crazy about going to Manhattan though is seeing like, tourists and cool old people, like 65 year old Arab guys wearing gold chains and shit. Like I find it interesting that Brooklyn nightlife has this “you can do whatever, be whoever, nobody cares” image, but actually ends up drawing a kind of specific crowd of people.

What’s the crowd?

Like 21-35 people wearing Uniqlo. I guess the word is “hipster.” Do you disagree?

Well, I don’t go out in Brooklyn, so I’m curious.

Okay.

But I don’t think I would associate “hipster” with Uniqlo.

What would you tell your average person going to Mood Ring or Nowadays or Black Flamingo to get them to cross the bridge?

I… have never been to any of the places you just mentioned. My Friday night and my Saturday night are the same every week. In the 10+ years that I’ve been in the city, though the venues have changed, it’s been the same crowds of people. I’ve always gone to Richie Akiva’s places, and I’ve gone to TAO Group places. Most recently, I go for dinner on a Friday or Saturday night at Lola Taverna or Little Prince, and then we’ll go to Socialista, which is above Cipriani, and then we go to Little Sister, which is a new TAO Group club. So that’s what I do, and I don’t know if I would try to convince people from Brooklyn to come to these things because they might not like it. If I went to clubs in Brooklyn, maybe I would feel like a fish out of water. For me, one of the things I like most is being a regular–I want to know the doorman, I want to know the bartenders, I want to know the different people that work there.

And also it’s very true that a lot of the places that I go to are notoriously very difficult to get into and the door people can treat you like absolute garbage, unless you spend thousands of dollars to buy a table. There’s this one place I go to where I have known the doorman for twelve years–I know this guy, right? And every now and again he’ll be like, “nah, you can’t come in tonight.” Just because.

You just let it roll off of you.

You can’t go out in New York City nightlife, like actual nightclub nightlife, and take it personally if the doorman is being a dick to you, because it’s really not personal. It’s all part of the mystique that they’re attempting to create.

It was the same thing with Studio 54 in the 1970’s, you know? They would turn down full-blown celebrities now and then so people would be like “oh my god, they didn’t let John Travolta in.” It keeps people talking, it keeps people intrigued.

Do you think that that mystique is alive right now?

If there’s one thing that I’ve learned it’s that every fucking generation of kid has nostalgia for the generation that they were not a part of. So people at Studio 54 were probably going there being like, oh yeah this is cool, but you know that club that was around in 1965 that our older friends used to go to? Now that was legendary. Everybody does that. In the 2000s, everyone was idolizing the 90s, in the 2010s everyone was idolizing the 2000s and the 90s, and in the the 2020s everybody’s idolizing the 2000s.

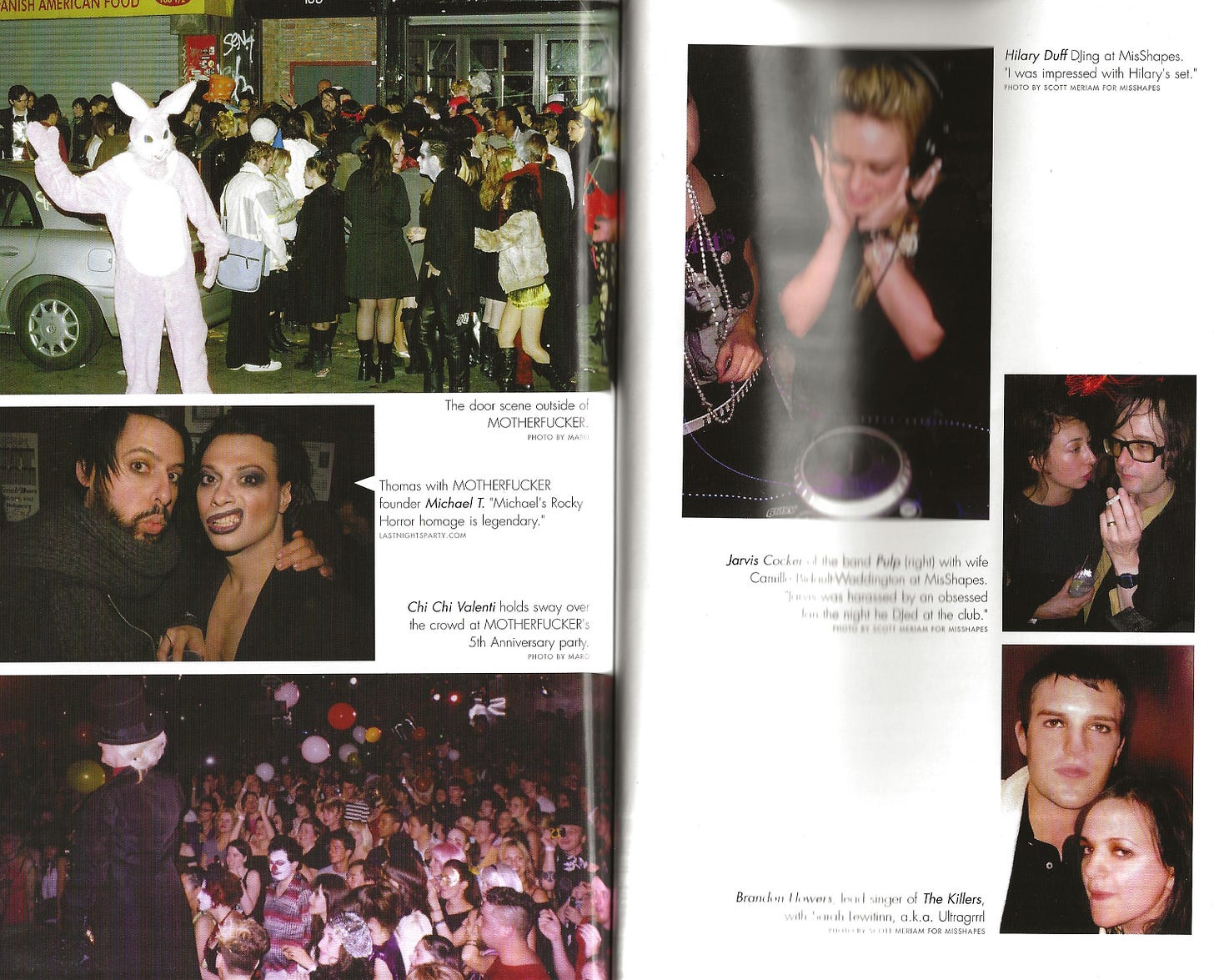

Re: indie sleaze, blurry scans from Confessions from the Velvet Ropes by Glenn Belverio, a book that makes everyone I show it to upset.

Do you really think that people in our era look back on the 2000s fondly? I guess I know what you’re referencing, but I have this book called Confessions from the Velvet Ropes, about this guy who was a doorman downtown in the 2000s, and it has a ton of pictures and shit in it, and every time I show people pictures from that book they’re absolutely disgusted. I feel like there’s a sense of mortification when it comes to 2000s celebrity culture that now people want to feel like they’re above, you know, this whole idea that with the pandemic, nightlife died, and now there’s a rebirth and it’s coming back again.

I hear what you’re saying; I really disagree with what you’re saying. There’s so many articles on the internet about how “indie sleaze” is coming back in such an extreme way, and “indie sleaze” was exactly what we went through in the early 2000s when Mark Hunter, the Cobrasnake, was running around Los Angeles and New York taking photographs at every single party. People are buying the same cameras that they used to use, and people are going for that same aesthetic, not just in clothing but in the way party photographs are taken.

But I would agree with you that nightlife has come back in a crazy way since the pandemic–the parties that I was associated with and throwing in July, August, September of last year fucking insane. I threw a party at New York Fashion Week in September last year, and something like 3000 kids showed up. Like, that is mind-blowing. We were at The Jane, and we had lines wrapped around both blocks.

Who do you model yourself after in nightlife? Who does it right?

It’s a difficult question for me to answer because I feel like there are lots of people who I respect in nightlife who often–nightlife people are seen as being really scumbaggy, and being creepy and being gross, but it doesn’t mean that they don’t know how to throw incredible parties.

I don’t really know the answer to that question. I think that I’m a little bit different from most people in my industry because I’m an anti-gatekeeper. I believe that anyone who shows up should get in if they want to. And the whole idea behind my “I Like You” parties is that yes, there are going to be celebrities there, yes, there are going to be models there, and yes, there are going to be cool kids and influencers and downtown characters and shit like that, but there’ll also be NYU students who are like “oh my god, I can’t believe I’m in the same room as the person I watched on that TV show.”

That’s really important to me, I want to give that experience to kids that I got when I first got to New York where it was like, “oh my god, I’ve only ever seen those people in movies and now I’m in the same fucking room as them.” That was such a massive thing for me, but the only reason I had those experiences was because I lived with a bunch of models and so I could go out with the promoters, so I automatically had entry into a world that was beyond anything that I traditionally would have been allowed to be a part of. So, I really want to give people that same experience that I had.

But the one guy I think has done an incredible job is Carlos Quirate. He’s the guy who started The Jane, he just started Pebble Bar uptown as well, with Pete Davidson and Mark Ronson. He and his partner Matt have done an incredible job of having longevity in this business, and they’ve been the coolest kids in New York and they’ve gone completely out of style, and now they’re having this massive resurgence in popularity and I think it’s really cool to see how they’ve rode the wave.

A lot of the nightclubs that I go to, some people would consider them to be super gross for other reasons, like they’ll only let girls in if they’re models, they’ll only let guys come in if they’re ultra-wealthy. But the advantage for someone like me as a DJ playing at venues like that is they pay you proper rates to play, like one dude might come in and spend $50,000 in one night, which means that they might not be as indie as some cool Brooklyn place that I’ve never heard of before, but they’re also not going to pay the DJ $100. You’re not playing at those places for clout and exposure, you’re playing at those places because it’s a serious job and you’ve reached a level where you can command a room like that and get paid properly to do it.

You say that people think that those places are creepy or gross. Are they creepy and gross?

I mean, I don’t find them creepy and gross, but they’re definitely not inclusive. In the same way that the fashion industry is not inclusive, you know. But when I say “not inclusive” I’m not talking about a race point of view, I’m talking about a social standing point of view. A lot of it is like, the cool kids get in. And nightlife is in its essence a business that is fueled by alcohol and sex, right?

And heartbreak.

And what?

And heartbreak, or like hurt feelings, or whatever.

Yeah sure, and I’m aware of what happens in that industry, but I also have loved nightclubs since I was a teenager. And in New Zealand, where I came from, you can start going out when you’re 18, so since the moment I was 18 and I could start going out, I have always really loved nightclubs.

[A note: After this interview was conducted, Isaac reached out and expressed to me that he regrets some of the things he said. In particular, he expressed that he didn’t mean to disparage any of his colleagues in the nightlife industry, and that it isn’t true that clubs he goes to “only let girls in if they’re models, [and] only let guys come in if they’re ultra-wealthy.” The interview has been edited and condensed for clarity.]